If you color art with contrast, Plymouth’s Juan Diego Perez la Cruz is a color wheel.

The architect/artist built a career in his homeland of Venezuela but moved in the midst of social unrest. “I was in survival mode,” says Perez la Cruz. “There were fires and mobs of people. If you put anything outside, it was stolen.”

Argentina was similar but completely different. “I lived two or three blocks from the stadium,” says Perez la Cruz. “When they scored a goal, you’d feel it in the building.”

At the polar opposite sits peaceful Plymouth, complete with a bird feeder in the yard.

Perez la Cruz has filled rooms with art and artfully worked empty rooms. He’s turned photographs into visual expressions and expressions into photographs. He has both reached out and offered a helping hand.

A plane ticket gifted by a friend sent Perez la Cruz from Venezuela to Argentina, where the artist’s art took a new approach. In offering a helping hand(s), Perez la Cruz works with the local organization Comunidades Latinas Unidas En Servico, (English translation: Latino Communities United in Service), also known as CLUES.

“I’m helping Latino artists create portfolios and doing portfolio reviews,” says Perez la Cruz. “If we can find a way, we’ll have an artist residency program.”

The ultimate goal is to get Latino-inspired art into new spaces.

“It’s difficult to get into those circles,” says Perez la Cruz.

Building and Being an Inspiration

Perez la Cruz himself serves as inspiration and his work is inspirational.

In Venezuela, his art explored the connection between memory, territory and politics. Specifically, his works serve as a link between shared memories and different cultures. He built his case with photos pieced together and apart.

In casting an artistic eye toward politics, Perez la Cruz traded flat art for performance art. “In an empty exhibit hall, I played the national anthem of my country,” he says. “I’d turn the lights on and hit the ground. I’d turn the lights off and turn them on again and fall back down.”

Picture a man crashing to the ground with the anthem of his country blaring in the background. The symbolism is clear.

While it happened a while ago and in the heat of the disruption, Perez la Cruz counts a particular exhibition as a favorite. “It was near the Caribbean, and the gallery didn’t have air conditioning,” he says. “It was awful and beautiful at the same time.”

Beginning to Grow

In Argentina, Perez la Cruz shared a house with his mentor. The experience changed his art. “In Venezuela, I had only attended technical schools,” says Perez la Cruz. “In Argentina, I was exposed to different techniques.” He was also exposed to new mediums. “I did more with videos,” he says.

During the pandemic, Perez la Cruz’ inspiration moved from photographing objects in his home to taking videos throughout the neighborhood. “I’d grab my backpack and go,” he says, while noting that his travel was limited because of the pandemic. “You could leave your home, but you couldn’t leave your neighborhood.” While this sounds confining, Perez la Cruz thought it to be liberating. “You didn’t want to go outside in Venezuela,” he says. “It was too dangerous.”

Getting Grounded

During an artist residency program in 2013 in Michoacán, Mexico, family photo albums and historic photographs were few and far between. In response, Perez la Cruz took a different tact in his cultural examination. Instead of incorporating historic photos into his art, he created his own.

Sans camera, he scanned faces with

a handheld scanner. “It looks like a wand,” says Perez la Cruz. The results, a collage-like effect, were magical.

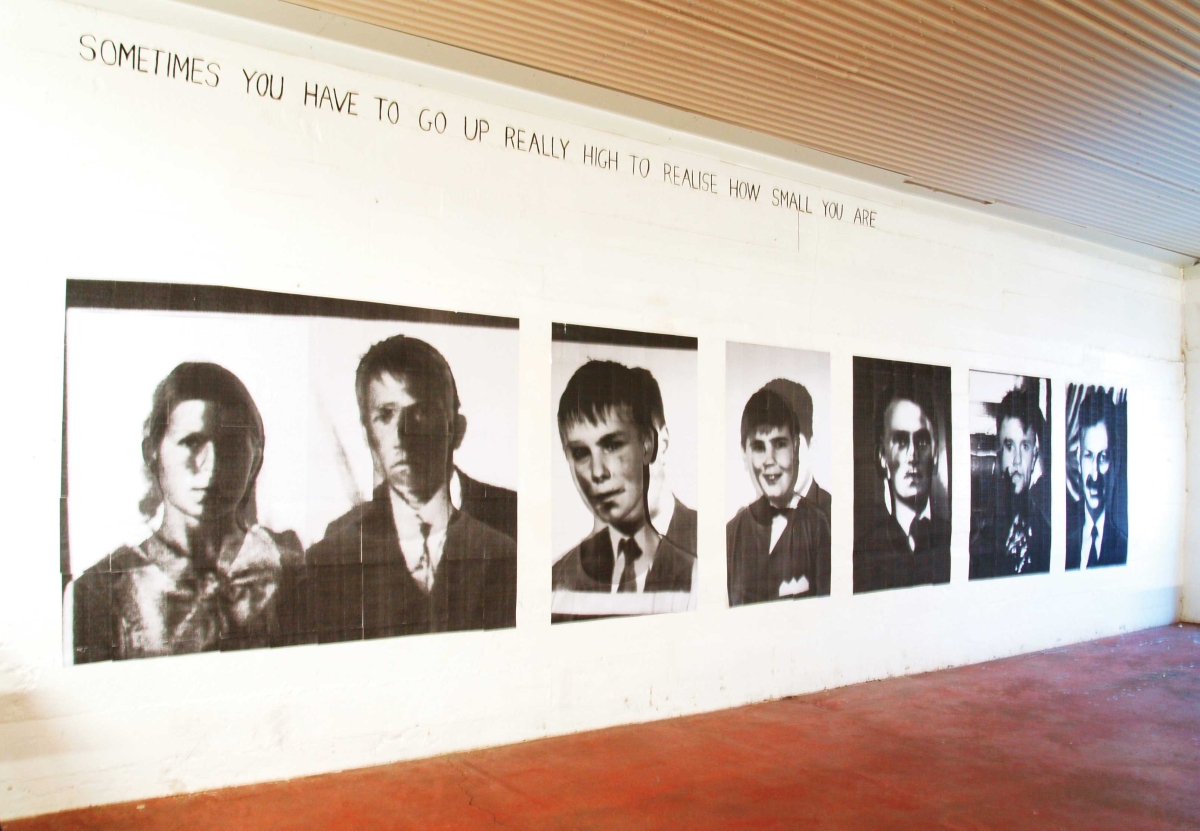

The artist experienced something completely different in another 2013 artist residency in Skagaströnd, Iceland. Of the town’s male population, half would leave and go fishing for six months, and half would stay in town. “After six months, they’d switch,” Perez la Cruz says.

Family albums, genealogy and histories were available for anyone to check out at the town library. “I was shocked,” Perez la Cruz says.

Needless to say, it made for a unique discovery. “I could link the town’s founding fathers with some of its youngest residents,” Perez la Cruz says. “Everyone stayed in that area their whole lives, and the children looked like their parents, who looked like their parents.”

A genealogic story, in pictures, would follow.

Settling Down

Perez la Cruz’ family moved to the U.S. in stages. First, his brother settled in Miami after leaving Venezuela in 2010. Later, Perez la Cruz’ mother came after recovering from open heart surgery in Venezuela. “She had heart issues and had been sleeping on the hospital floor for months,” Perez la Cruz says.

Perez la Cruz’ father would follow his wife to the U.S. after losing his job in the sugar industry. “He signed a referendum about new leadership,” he says. “They published everyone’s name in the paper, and anyone working for the state was fired.”

“I was [the] last one [to move to the U.S.],” Perez la Cruz says. “I moved in with my brother after he moved to Plymouth.”

El Mural de los Idos (The Mural of the Gone)

Q+A with Perez la Cruz

Best thing about living in Minnesota?

He wanted to say snow, but he couldn’t. As a medium, snow can be tricky. “It’s easy to play with, but it’s tough to work with,” says Perez la Cruz. “I hold it for a few minutes, and my hands get too cold.”

In reality, he loves urbanism and green spaces. “I do projects and journal every time I go to a new park,” he says.

Favorite space?

Without hesitation, Perez la Cruz lists the Weisman Art Museum on the University of Minnesota Twin Cities campus as his favorite. “To anyone who has studied architecture, the Weisman building is an icon,” he says. “Before seeing it in person, I had only seen pictures on my phone. It’s different than I thought it would be, but amazing.”

He also has a list of other buildings he’d like to visit. “I’m finding time to go to those, too,” he says.

Will he visit home again?

“I would like to go back to Argentina, but that chapter is probably closed,” he says. “Because of my visa, I would have to first go back to Venezuela and get permission to go to Argentina. That could take a long time.”

In the meantime, a second chapter in Plymouth looks to be a good read.